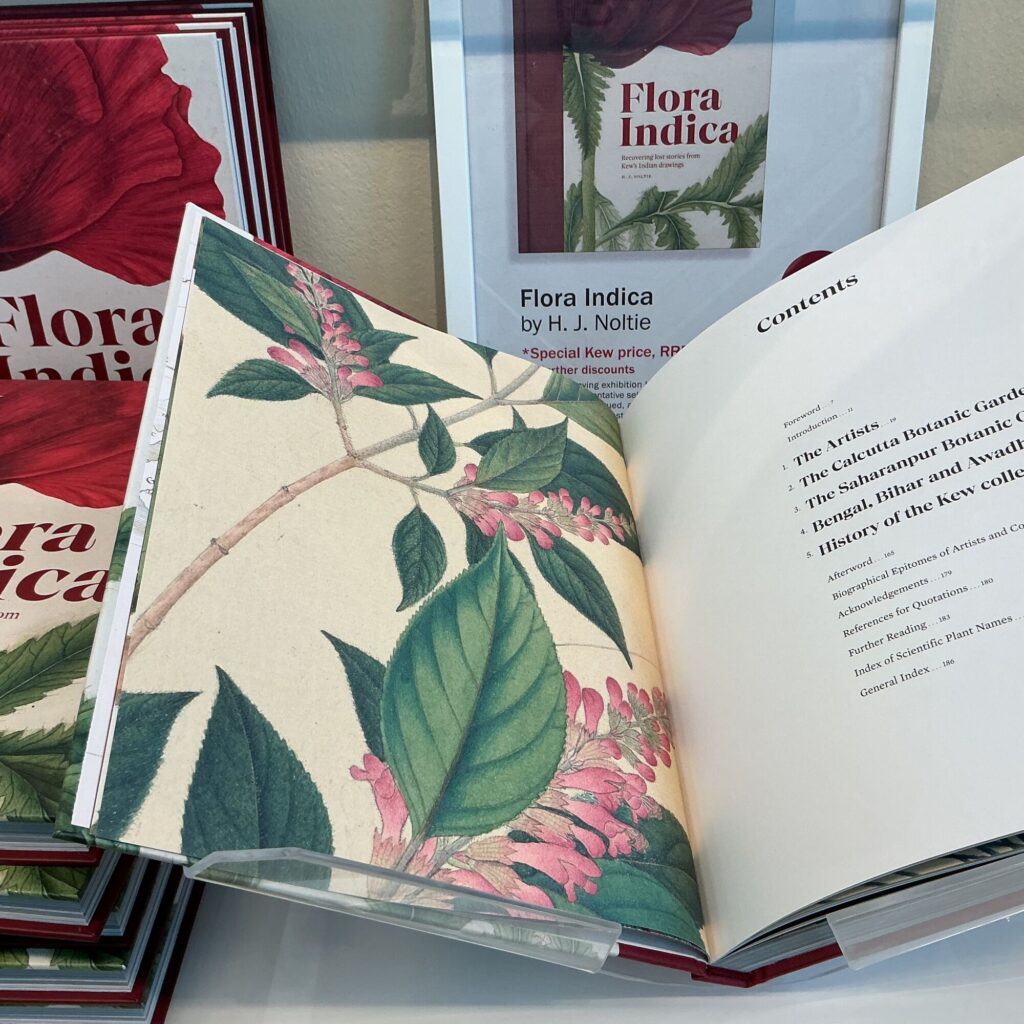

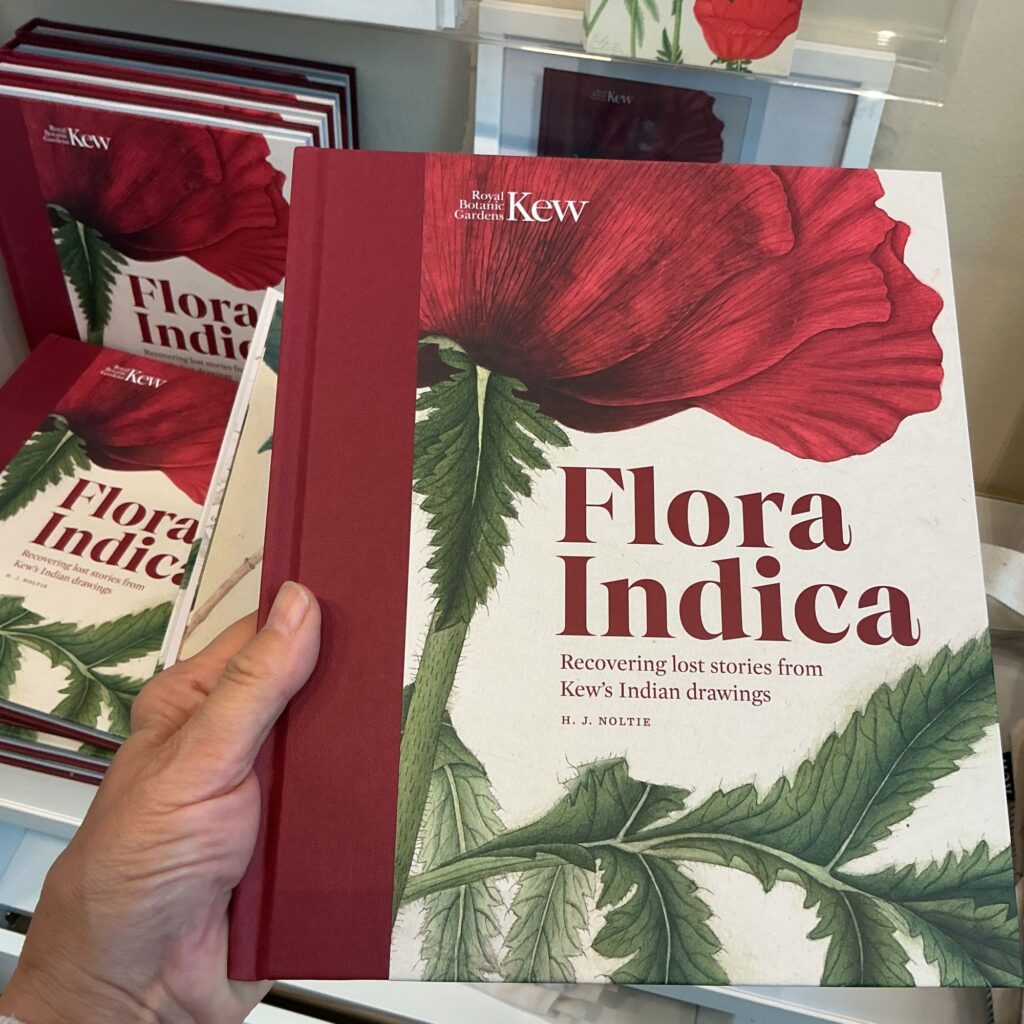

Flora Indica

I’m back in London and excited for a new exhibition of botanical paintings at the Shirley Sherwood Gallery at Kew Gardens. The exhibition is as amazing as ever, and this time it celebrates the rich biodiversity of South Asia. It takes visitors from the palm groves and banana farms of the tropical south to the rhododendron forests of the Himalayas in the north.

Right at the beginning of the exhibition, I was struck by the date of the watercolors. They are from 1790 – 1850, when India was a British colony.

In 1786, a botanical garden was established in Kolkata. It was part of a scientific effort that preceded the emergence of botanical watercolour in India. British botanists, but also doctors, brought with them the practice of botanical painting, which was intended to accurately document newly discovered plants. They employed talented local artists who were trained in traditional Indian techniques. Under British guidance, they mastered the principles of scientific illustration and the technique of watercolour, and so these interesting paintings could be created. They came to Kew by various routes, some from private collections, others through the Company’s India Museum in 1879.

It is very sad that the names of Indian artists have been neglected and often not even recorded. They have been referred to collectively as “Indian Artists” or “Musaver” or only the name of the commissioner of the work has been given. Yet the names of some of them have now been identified thanks to long and careful detective work in the archives of Kew and Kolkata.

One of these artists is Vishnuprasad, whose 1825 watercolour of a Chinese fan palm (Livistona chinensis) has become the iconic painting of the exhibition. Vishnuprasad was probably from Bengal and was one of the experts on the team of Indian botanical artists in Calcutta. Attributing the name of the artist to such an old work is a major achievement in the effort to restore historical justice and recognition of Indian artists. Unfortunately, for most of the 52 botanical watercolours on display and the 7,000 illustrations in the Kew archive, the names of the artists remain unknown.

The aim of this exhibition and the accompanying book by Dr. Sita Reddy, who is the curator of the exhibition with Dr. Henry Noltie, is to correct historical omissions and injustices and to point out the indelible.